At about 2 a.m. on August 20th 1852 the ships Atlantic and Ogdenburg collided on Lake Erie. SS Atlantic sank, taking with her about 300 of her 500 passengers, mainly immigrants on their way to the US. This was one of the first major disasters involving Norwegian immigrants, almost 70 of those who died were on the last stage of the journey from Norway to various destinations in the Midwest. One of those who survived the accident was Erik Iversen Torstad from Øyer. In a letter home, dated November 9th 1852, he gives a detailed account of what happened.

Erik Iversen Thorstad was born in Øyer on September 3rd 1829 on the farm Torstad in the Tretten area. He was the youngest son of Anne Larsdatter Thorstad and her husband Iver Hanssen Lie, originally from Gausdal. Erik was confirmed in the Tretten church on June 9th 1844, and is recorded in the church book as having left Øyer for the US on June 10th 1852. He probably left Norway on the sailing ship Argo, which sailed from Christiania (now Oslo) on June 16th and arrived in Quebec on August 12th 1852.

For many years the route from Christiania to Quebec was the chosen alternative for Norwegian immigrants going to the Midwest. When arriving in Quebec the immigrants faced another long journey, which went by railroad and wagon, for some also partly by foot, but first and foremost by ship on the Great Lakes. This is the part of his journey that Erich Iversen Thorstad describes in his letter home, including the disaster he became an eyewitness to en route.

The white line shows the route Erik Iversen Thorstad and many other Norwegian immigrants took from Quebec to Milwaukee. The white star marks where SS Atlantic sank in 1852.

The letter

From Erik Thorstad, Town of Ixonia, Jefferson County, Wisconsin, November 9th 1852, to parents and siblings in Øyer.

"Our good leader, Captain Olsen, contracted with a company to carry us and our baggage to Milwaukee for seven dollars for each adult and half fare for the children. On August 14 our baggage was brought aboard a large steamboat and we left the evening of the same day at five o'clock. At six the following morning we came to a town called Montreal. Our skipper, who had accompanied us to this place, then took leave of us. Shortly after he had gone, an accident occurred; a man from Valders fell overboard as he was bringing his baggage of the boat. It was right pitiful to see how he struggled. And no means were on hand whatsoever with which to save him. Arrangements were finally made for dragging, whereupon he was found, but by then he was dead. This event was all the more tragic since he had a family, which mourned its lost provider.

At this place our baggage was taken in wagons about one English mile, and then we travelled by steamboat for about twenty-four hours. We passed through many locks which we looked at with wonder. Since we could not get a boat the day we reached this place, a town named Toronto, our baggage was unloaded on the warf, and the immigrants, except myself and a couple of others, spent the night under open sky. At eight the next morning we left by steamboat, and in the afternoon of the same day we landed below Niagara Falls near the ingenious hanging bridge made of steel cables. Many of us had decided to go near this masterpiece and inspect it, but we had to forego this, as our baggage was immediately loaded on wagons and drawn by horses on a railway for about sixteen English miles. On this trip we had an opportunity to view the great and much-famed waterfalls, Niagara.

We came to the town of Kingston late in the evening. There, too, our belongings were placed on the warf, and the same ones as before found lodging on the wharf, while I and two of my comrades lodged in town. Some of the immigrants left for Buffalo on a small steamboat at five o'clock the next morning. At five in the evening the boat returned and got the rest of us. Buffalo is avery large town with about 50.000 inhabitants, but I did not think it was really a very pleasant place. Along the wharves, especially, it was quite unwholesome. From Quebec to Buffalo some seventy-five poor people from Valders had free transportation. But here they had to remain as they did not have enough money to pay passage across the Lakes.

We left Buffalo on a large steamer, called the "Atlantic", in the evening of the same day - August 12 - at eight o'clock. The total number of passengers was 576, comprising 132 Norwegians, a number of germans, and the rest Americans.

Since it was allready late in the evening and I felt very sleepy, I opened my chest, took off my coat and laid it, together with my money and my watch, in the chest. I took out my bed clothes, made me a bed on the chest, and lay down to sleep. But when it was about half past one in the morning I awoke with a heavy shock. Immediately suspecting that another boat had run into ours, I hastened up at once. Since there was great confusion and fright among the passengers, I asked several if our boat had been damaged. But I did not get any reassuring answer. I could not belive that there was any immediate danger, for the engines were still in motion. I went up to the top deck, and then I was convinced at once that the steamer must have been damaged, for may people were lowering aboat with the greatest haste. Many from the lowest deck got into the boat directly, and as the boat had taken in water on being lowered, it sank immediately and all were drowned.

Thereupon I went down to the second deck, hoping to find means of rescue. At that very moment the water rushed into the boat and the engines stopped. Then a pitiful cry arose. I and one of my comrades had taken hold of the stairs which led from the second to the third deck, but soon there was so many hands on it that we let go, knowing that we could not thus be saved. We thereupon climbed up to the thrid deck, where the pilot was at the wheel. I had altogether given up hope of being saved, for the boat began to sink more and more, and the water almost reached up there. While we stood thus, much distressed, we saw several people putting out a small boat, whereupon we at once hastened to help. We succeeded in getting it well out, and I was one of the first to get into the boat. When there were as many as the boat could hold, it was fortunately pushed away from the steamer. As oars were wanting, we rowed with our hands, and several bailed water from the boat with their hats.

A ray of light, which we had seen far away when we were on the wreck and which we had taken for alighthouse, we soon found to be a steamer hurrying to give us help. We were taken aboard directly, and then those who were on the wreck as well as those who were still paddling in the water were picked up.

his boat, which was the one that had sunk ours, was of the kind known as a propeller, driven by a screw in the stern. The misery and the cries of distress which I witnessed and heard that night are indescribable, and I shall not forget it all as long as I live. The number of drowned were more that 300, of whom sixty-eight were Norwegians. Many of the persons who were in the first class were drowned in their berths or staterooms. The Norwegians who were rescued totaled sixty-four, but most of them lost everything. I saw many on board the propeller who had on only shirts. The newspapers blame the command of the "Atlantic" for this sad event and reproach them most severely and accuse them openly of having murdered three hundred people.

The propeller soon delivered us to another steamboat which brought us to a city called Detroit, where we arrived at eight the next morning. After we had got some provisions for our journey, we continued on a steam train. Late in the evening we reached a large torn in Illinois, called Chicago, where we spent the night and had everything free. On the trip there, we saw many beautiful farms and orchards as well as many attrative buildings. We left the following morning by steamboat, and after five or six hours we reached Milwaukee. That was on the twenty-second of August. We stayed with a Norwegian where we remained until the twenty-eight of the same month. Since the city had taken up a subscription for our support, we lived free of charge, and in addition each person received elen dollars in money. With this money I bought two coats, a pair of trousers, a pair of shoes, tho shirts and a bag.

From Milwaukee I went by steam train twenty to twenty-five miles without charge, and then I footed it, reaching Østerlie's the thirtieth of August. There i have since remained. I am well and have, God be thanked, been in good health all the time. Allthough I have lost all my possesions, I have not lost courage. The same God who has helped me in the time of danger will, I hope, continue to be my protector."

The aftermath

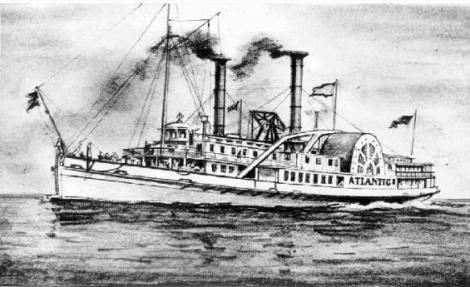

SS Atlantic, built 1848, courtesy of Institute for Great Lakes Research, Bowling Green State University.

As Erik Thorstad writes in his letter that the press blamed the captain and the owners of the Atlantic for the disaster. The inquiry held into the loss of the ship found that the steering system of both ships was in order, and that the collision was due to a human error, but drew no conclusion as to which ship had caused it. Two theories remain, either that one or both of the pilots had made a careless miscalculation, or that the collision was a result of a deliberate maneuver to injure a rival boat. In a court case brought by the owners of the Atlantic against the owners of Ogdenburg the US Supreme Court in 1856 ruled that both ships were equally to blame for the disaster.

The traffic on the Great Lakes was a lucrative business for the ship owners and speed was a decisive element in the competition to attract more passengers. The fastest ships were powered by steam, and in the quest for speed and new records the boilers often were forced to an extent that affected the safety of the passengers. Several serious accidents involving boilers that were overloaded had occurred earlier that summer and the means of preventing such accidents and safety issues in general were already widely discussed in the press.

Less than two weeks after the loss of Atlantic on Lake Erie, the US Congress passed a bill providing for the licensing and inspection of steamboats and a number of safety regulations. These included regulations as to the pressure in the boilers, as well as the carrying of lifeboats, life preservers and other aids in case of trouble.

There is nothing to indicate that the Atlantic disaster had anything to do with her boilers and Erich Thorstads letter indicates the presence of lifeboats. Atlantic was however very much a part of the competition taking place on the Lakes involving speed, and at the time of her disaster held the record of being the fastest ship between Buffalo and Detroit (16 ½ hours). This might explain some of the criticism facing her owners after the loss.

Atlantic's passengerlist was lost when she sunk. We owe the knowledge of the number of Norwegian immigrants aboard, and the names of those who perished to Stephen Olson of Manitowoc, Wisconsin (originally from Valdres) who accompanied the Norwegians as a translator and guide. His list of casualties with names and hometowns was published in the periodical "Skandinaven" on October 27. 1852. According to this list 3 came from Vang, 36 from Slidre, 23 from Aurdal and 5 from Toten, altogether 67 persons.

The wreck of the Atlantic today rests in 165 feet of water on the Canadian side of the border south of Long Point, Ontario. Since shortly after the disaster the wreck has been a target for salvage operations. The most important cause of this was Atlantic's safe, which contained approximately $35.000 (in 1852 dollars) of American Express gold. The safe was brought to the surface by divers in 1856, which was a feat in itself, since dives below 40 feet was seen as impossible prior to this!

SS Atlantic was only four years old when she sank, and known for her luxurious interior. The first class state rooms were said to be decorated with gold gilding, tapestries, and carved rosewood furnishings. These rumors attracted bounty hunters and several attempts were made to retrieve items from the wreck. One of the more exotic of these attempts involved an submersible diving bell. The attempt failed, and the wreck of the submersible now rests on or near the deck of the Atlantic.

The wreck was then forgotten, until its rediscovery in 1984 by a local Canadian diver, who retrieved several hundred artifacts, mainly of historic value. A California based salvation company used the buoy placed to mark the find to explore the site and claim the rights to the wreck. A California court granted this right in 1992. Canadian authorities opposed this ruling and finally won the case, the court finding that the wreck of SS Atlantic rests in Canadian waters and is abandoned by it's owners. The Ontario Government, who the courts deemed to be the owner of the wreck, has promised that artifacts from the ship will be made accessible to the public.

As opposed to too many of his co-travelers Erich Iversen Thorstad arrived safely at his destination. Eventually he left Ixonia and headed further west, to La Crosse in Wisconsin, where he became a grocer. In 1888 he returned to Norway for a visit, at least we find him and his wife (also Norwegian) as passengers on the ship Rollo, returning from Christiania to New York.

Erich Iversen Thorstad died in January 1908, and is buried at Oak Grove cemetery in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

© Nanna Egidius