Seminar Paper Department of Economics Harvard University Spring 1989; NUPI-report no. 130 July 1989. 58 pages. ISSN no.0800-0018.Strategies for Reducing U.S. Oil Dependency

(pdf - 133 KB),

SUMMARY:This report focusses on strategies for reducing the costs of U.S. dependency on imports of crude oil. The model presented demonstrates how security of supply can be considered as an externality in the imports of oil. On the other hand, if domestic production is increased in order to reduce imports, externalities destructive for the environment may increase. The analysis shows how the optimal level of domestic production, imports and consumption of oil can be found taking the externalities of security of supply and the environment into consideration.

In order to reduce the sensitivity and vulnerability dependence on foreign oil, the paper argues in favor of a continuous reliance on the Strategic Petroleum Reserves (SPRs). Use of the SPRs dampens the immediate shocks in a situation of disruption and reduces the sensitivity dependence. However, a heavy reliance on stock policy is not necessarily reducing the possible longer term vulnerability dependence on foreign oil. Therefore, also the level of imports should be considered reduced. The report argues that domestic U.S. production could not (of reserve and cost reasons) or should not (of environmental reasons) be increased. Thus, a reduction in imports of oil should first of all be met by reduced consumption. A combination of a tariff on imports and a tax on domestic production have the potential to regulate imports and domestic production in an optimal manner taken the externalities into consideration. However, the report recommend a gasoline tax. The argument is that it probably will be politically difficult to introduce taxes on domestic oil producers simultaneously with the introduction of a tariff. As a single remedy introduced, a gasoline tax will usually be more optimal than a tariff.

NOTE: For a discussion of military options for reducing the problems connected with oil dependency, see see Austvik "The War Over the Price of Oil: Oil and the conflict on the Persian Gulf", International Journal of Global Energy Issues Vol.5, No.2/3/4, pp.134-143. London October 1993. ISSN 0954-7118 (http://www.kaldor.no/energy/GLOB9205.pdf).

Remark: You are welcome to download, print and use this full-text document and the links attached to it. Proper references, such as to author, title, publisher etc must be made when you use the material in your own writings, in private, in your organization, in public or otherwise. However, the document cannot, partially or fully, be used for commercial purposes, without a written permit.

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 1. U.S. DEPENDENCY ON OIL IMPORTS

2. EXTERNALITIES IN IMPORTS AND PRODUCTION 1.1. Dependency, Sensitivity and Vulnerability

1.2. The U.S. Oil Balance3. POLICY OPTIONS 2.1. The Security Problem

2.2. Environmental Concerns

2.3. Combining Security and Environmental Aspects4. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 3.1. Oil Import Fee

3.2. Gasoline Tax

3.3. Conservation and Switching Policies

3.4. StockpilingREFERENCES

INTRODUCTIONAgain, the U.S. is becoming more and more dependent on foreign oil. Consumption is increasing at the same time as domestic production is decreasing. Imports were in 1988 above the level prior to the first oil price shock in 1973/74, even though still below the level prior to the second, starting in 1979. Most observers agree that the market for crude oil today does not seem to involve any great danger of a major disruption. But experts have been wrong before. Nobody foresaw the second price shock in 1979/80 starting after Ayatollah Khomeiny's take-over in Iran. If the trend in increasing U.S. imports continues over the next years, the U.S. may face as great or even greater dependency on foreign oil as prior to the second shock.

This paper focusses on strategies for reducing U.S. dependency on foreign supplies of crude oil. Both possible modifications of the trend towards increasing imports as well as the immediate emergency problems in case of a disruption will be discussed.

The first Chapter makes an attempt to distinguish a country's "normal" dependence on imports of a commodity from sensitivity and vulnerability dependence. The second part of Chapter One shows figures for U.S. consumption, production and reserve development.

The second Chapter discusses how the risk for disruptions in supplies may be viewed as an externality in imports and, thus, consumption of oil. The model presented also demonstrates how environmental externalities as a result of increased domestic production can be evaluated together with the security-of-supply problem. This is of particular importance if the security problem is sought solved (partly) by increased domestic production.

Chapter Three discusses how fiscal policies and conservation and switching strategies can be used in order to reduce imports. Special weight is assigned to the role of stocks as a means in an emergency situation. Some foreign policy considerations are also included in the Chapter.

Chapter Four summarizes the discussion and suggests some policy options. The options are discussed with emphasis on the effect they have on variables as dependency, vulnerability, the budget, the environment, administrative and political feasibility and oil exports and importers, respectively.

1 U.S. DEPENDENCY ON OIL IMPORTS

The situation in the oil market and the likelihood for and magnitude and duration of disruptions will be taken as exogenous variables in this paper. We assume that there is some possibility that a crisis may occur again. Our objective is to focus on how a given situation of disruption can be dealt with and prepared for.

However, the type of crisis will affect the choice of policy. Under which circumstances should a possible new price shock be a serious concern? How will the choice of policy be affected by the gravity of the potential crisis? Clarifications of the dimensions of sensitivity and vulnerability interdependence between nations may give some help in sorting out these questions.

1.1 Dependency, Sensitivity and Vulnerability

Dependency can be defined as a situation where a nation does not possess the capacity to produce 100 per cent of its own needs. According to this definition, most countries are dependent on imports of a whole range of commodities. Dependency is thus a normal state of affairs. A country can be sensitive, vulnerable or neither in it's dependency of the commodity when it's price or availability changes. This will be a function of the magnitude and duration of the change and the country's ability to adjust to the changed environment. It also varies with the importance of the commodity in the economy. Obviously, changes in the supplies of oil is in and by itself more important for most countries than changes in the supplies of for example fishing hooks.

Sensitivity dependence is measured by the degree of responsiveness within an existing policy framework. It may reflect the difficulty to change policy within a short time and/or bindings to domestic or international rules. Vulnerability, on the other hand, is a measure of the ability to adjust to changes in the availability or price of a commodity on which the country depends. Thus, vulnerability is represented by the costs caused by external price shocks even after policies have been altered. In economic terms, vulnerability can be represented by the potential for significant losses of output or welfare.

A country can become more sensitive or vulnerable in a given state of dependency if the commodity originates from one powerful state as opposed to if it is multilaterally dependent. It will also depend on whether the supplying nations are antagonistic or friendly in their relations to the purchasing country or not. Foreign politics will therefore be an important instrument for reducing dependency in addition to the domestic measures. For oil, however, it is important to notice that a sensitivity or vulnerability dependence can occur even if a country does not import oil from any 'risky' source at all. If the price of imports from 'secure' sources varies with the insecure sources, as is the case for oil, the problem still persists. During a disruption anyone can normally purchase the oil they want. The problem is that this oil costs so much in a crises that serious damages are brought on to the country's economy. And the oil market today functions so well that a price change in one part of the world, quite immediately affects prices anywhere else. Therefore, the U.S. can be rather independent on insecure oil supplies (e.g. from the Persian Gulf) and still be dependent on price fluctuations (e.g. on Mexican, Venezuelan, Canadian or North Sea oil). Thus, for oil, the security of supply issue can be limited to a question of costs for the society when the price changes.

The costs of the dependency on imports of a commodity are measured both by the increased expenditures on imports as well as the costly effects of changes on societies and governments. The change in policy will depend on political will, governmental ability, resource capabilities as well as international rules. A sensitivity dependence occurs in "the short run or when normative constrains are high and international rules are binding". A vulnerability dependence occurs when "normative constraints are low, and international rules are not considered binding". Thus, a country's sensitivity can be significantly different from it's vulnerability.

As dependency on imports is a normal state of the economy, government policies should aim at eliminating or reducing sensitivity and vulnerability. The two may be interlinked however; reduced import of oil reduces dependency at the same time as it reduces the possible sensitivity and/or vulnerability.

In the model presented in Chapter Two, we relate the security problem to the magnitude of imports. The quality of this measurement for sensitivity and/or vulnerability dependence can be modified. If two countries import the same quantity of oil and one of them has the option to shift to alternative energies or increase domestic production and the other not, the first country is less vulnerable than the other. This ability to shift depends both on the elasticity of demand and, as in the case of U.S., on the elasticity of domestic supply. The speed of the adjustment of demand and supply is important in determining the degree of dependency in the short and the long term, respectively. If a country changes from being inelastic in it's demand for imports in both the short and long term to inelastic in the short and elastic in the long term, the country's dependence on imports may change from vulnerable to sensitive.

Also the energy intensity in the economy is important. The U.S. has for example a much higher consumption of energy pr. unit of GNP than in Western Europe. Changes in the oil price will, therefore, have larger impact on U.S. economy than on Western European economies. The level and use of inventories will also affect the dependency. A release of inventories can be perceived as equivalent to an increase in domestic production and reduces the damages to the economy in the short run. The role and use of inventories will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.4.

Thus, when we use the magnitude of imports as a measurement of sensitivity or vulnerability dependence in Chapter Two, many other factors are assumed to be constant. Even if this is a simplification, it illustrates an important dimension of the problem.

1.2 The U.S. Oil Balance

The U.S. is one of few countries in the Western world that have not increased taxes on gasoline and other oil products as a response to the decline in world oil prices in 1986. The consumers have benefitted immediately and fully from the price drop. Thus, demand has increased with some 400,000 barrels a day (O.4 mbd) in each of the three years 1986-87-88. Western Europe has increased gasoline taxes to an extent that consumers have experienced rather small declines in prices. The result has been that the increase in consumption in Western Europe has been more or less insignificant compared with changes in the U.S..

However, while the drop in energy prices benefitted consumers and the overall U.S. economy, it undercut the oil industry. A number of 'stripper-wells' have been closed down, reducing production each of the last three years with some 200,000 barrels per day. The U.S. has proved to be the world's highest cost producer. Furthermore, with low oil prices and better drilling prospects abroad, the industry has to a large extent found it profitable to devote exploration efforts in other countries than in the U.S. Long lead times between exploration, production decisions and actual production indicate that it may take several years to turn this trend, if so was decided.

In sum, the result has been an increase in imports in the size of 2 mbd since 1985. Consumption in 1988 was estimated to almost 17 mbd and production to 8.2 mbd, with total imports amounting to ca. 6.2 mbd, and 8.8 mbd if products are included. Thus, the increase in total petroleum imports has been some 30 per cent and crude imports some 45 per cent over 3 years.

Seen in a longer perspective, i.e. the last two decades, oil production has, in fact, been rather stable in the U.S., varying between 8 and 9 mbd. After a drop in 1974 and 1975, consumption, on the other hand, rose somewhat in the second part of the 1970s, but has been dampened for many years in the 1980s. With low oil prices, demand is increasing again and in 1987/88 it reached the level of 1973/74, even though it is still below the level of 1977/79.

Could the U.S. increase domestic production of crude oil in order to reduce imports? Are the reserves big enough? It is normally not easy to determine what are the reserves in an oil field or for a country. It may, however, be helpful to distinguish between 3 different concepts. Current reserves are those that are known to be profitably extractable at current prices. Potential reserves are defined as a function of the price people are willing to pay. Thus, the size of the potential reserves are changing with the price of oil. The endowment is the natural occurrence of resources in the earth's crust. The third concept is geological rather than economic, and represents the upper limit on the availability of terrestrial reserves. Theoretically, the price of oil can become so high that a resource can be physically depleted. However, in practice, when the price becomes too high, backstop prices will set upper limits for how high the price of oil can be and thus how much of the endowment can be extracted. The current and potential reserves set the frames for the economic scarcity of a reserve. The higher the price of oil, the larger the current reserves. The size of the potential reserves depends, on the other hand, on the expectations made for the development of the oil price.

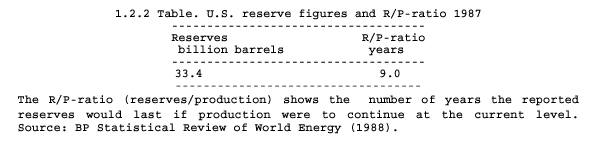

When we in addition to the problems of definitions take into consideration the technical difficulties in measuring underground reserves, the interest for oil companies to estimate low reserves in order to push depreciation costs ahead in time and possible political interest in estimating low reserves of security reasons, reserves figures must be studied with great care. Oil reserve figures for the U.S. are excellent examples of this problem. For 25 years the reserve figures have shown a steady readjustment and almost every year the U.S. has had 8-10 years left to produce before the reserves were totally depleted! At the end of 1987 the figures were reported to be:

If decision-makers should base policies on these figures, quite dramatic conclusions should be drawn. Continuous readjustment of reserves tells us that it would be premature. However, the figures indicate that the endowment of oil in the U.S. is not infinite. Even in huge price hikes as in the seventies, production proved to be rather inelastic. Substantial upwards adjustments in production do therefore not seem to be a policy that is sustainable in the long run. Therefore, we argue that the size of U.S. oil imports can first of all be regulated by reduced consumption.

2 EXTERNALITIES IN IMPORTS AND PRODUCTION

The situation for an oil-consuming country with both domestic oil production and some imports, can be illustrated as in the graph 2.0.1. Long run supply curve for U.S. domestic production is represented by the upward sloping curve CAE. Domestic short run supply is assumed much more inelastic, as illustrated by the vertical line through A. This is because it takes time for producers to adjust to a new price environment. Uncertainty about a new price level may also delay producers' decision of changing output. Therefore, a change in the price of oil may not affect output significantly in the short run.

Demand is illustrated by the downward sloping curve EB. This curve also represents the marginal social benefit of consuming oil. The price set in the world oil market is illustrated by the straight line, Popec = p. U.S. production takes place in A and consumption in B. Quantity imported is represented by the distance B-A. With no import, equilibrium will be in E, with much higher price and lower quantities. The curves are drawn linear for simplicity reasons.

2.1 The Security Problem

If a disruption occurs, the price of crude oil moves from p to p# as illustrated in the graph 2.1.1. The loss in consumer surplus of the price shock will be the area NDBO. Because of rigidities in the expansion of domestic production, U.S. suppliers would not be able to immediately increase production to K along their long-run supply curve. In the short run they will produce the same as before, but at a higher price, i.e. in M instead of in A. They gain the area NMAO as a result of the increased prices. If they had been able to move to K, they would have gained NKAO, which is an even larger area.

The net (short run) loss to society is represented by the area MDBA. DBP is deadweight loss for consumers, and MDPA transfers of wealth from domestic consumers to foreign producers. In the longer run, if the new price level is sustained, domestic producers will adjust to K and gain MKA in addition to NMAO. Therefore, the area MKA is benefits for foreign producers in the short run and for domestic producers in the longer run. A price shock therefore causes larger damage to the total economy in the short than in the long run. Consumers loses the area NDBO in both the short and long run.

Let's assume that the imported quantity B-A is viewed as a security problem, because of these losses in consumers' surplus in case of a disruption. We assume that the security problem is considered to increase as quantity imported is increasing. One way to interpret the security problem connected with imported oil is that the individual consumers, by buying oil and making investments and behavioral adjustments with the expectations that oil shall continue to flow at current prices, is imposing an externality to the society. They do not take it into account, because they are to small to influence the situation, the costs of increased stockpiling, emergency plans, or possible military interventions in the Persian Gulf to secure the supplies.

The social cost they impose on society is illustrated by the upward sloping curve AFG in the graph. The shape and slope of it will be influenced by many of the factors discussed in Chapter 1.1. As imports grow, the costs to society are increasing in order to minimize the likelihood of severe disruptions and to deal with the disruptions if they occur. The U.S. government could improve national welfare by changing consumption and domestic production decisions to reflect the total costs of oil imports, not just the private costs reflected in market transactions.

With these external costs included, consumption should have been in F where marginal social costs equal marginal social benefits. In B, the point which the market realizes, marginal social benefits equal marginal private costs. In this point, marginal social costs exceed marginal social benefits, and the loss is represented by the shaded triangle BGF.

U.S. security of supply problem is, in this model, a function of the U.S. dependency (quantity imported). As discussed in Chapter 1, this is a simplification of the real sensitivity and vulnerability problem. The problems of dependency on foreign oil not only varies with imported quantity, but also with the stability of the oil market, the number of suppliers in the market, the elasticity of demand and supply (short and long run), the energy intensity (for example measured by the quantity of oil needed per unit of output or GNP) in the economy and many other factors outside this model. Nevertheless, a partial consideration of the problem may be helpful in order to design appropriate policies in a situation where other variables can be thought of as rather constant over the relevant time horizon.

If by some means or another, the U.S. government succeeded in realizing the price p* for consumers with import prices remaining as before (i.e. by taxes or tariffs), point F would be realized for consumers. Consumption in F is socially optimal, as the marginal social cost curve expresses how much society is willing to pay in order to reduce the negative effects of import dependency. If point F was achieved by a tariff domestic producers would increase production up to point H (after some time).

If a disruption occurs in this situation, with prices shooting to p#, consumers would lose NDFO', an area much smaller than NDBO. Producers would gain the area NLHO' in the short and NKHO' in the long run. The net loss for the society would be LDFH in the short run and KDFH in the long run (supposing that the remedy, e.g. the tariff is removed when prices went up to p#). The position of the marginal social cost curve implies that the losses LDFH and KDFH, for the short and long run respectively, are acceptable risks to take in case of a price shock. The damage, if a disruption occurs, is reduced to an acceptable level at an acceptable cost.

A release of stocks could also improve the situation. A stock release of the size L-M would be equivalent to a shift in the short run supply curve from S1 to S2. The short run situation would then be the same as the situation as if prices before the disruption were raised to p*. The question is, however, whether stocks can be large enough to cover this gap over the time period needed to increase domestic production. We have argued that the long term U.S. supply curve seems rather inelastic to changes in prices. Therefore, a stock release can only serve as a relief for a shorter period of time. The loss for the society will be larger if the U.S. relies only on stock policy to take care of the problem as opposed to adjustment of the size of the import (as well) in a long-lasting disruption situation.

2.2 Environmental Concerns

However, if the security problem is (partly) sought solved by increased domestic production of oil (assuming U.S. oil producers really can increase production), "unacceptable" environmental problems could be the result. The more marginal oil fields are, they will have to be developed at a higher cost and sometimes with increased environmental externalities.

Let's assume that the marginal environmental cost is increasing with quantity produced. The curve through S, R and Q in the graph 2.2.1 illustrates the marginal social costs of domestic oil production. Production represented by the point A imposes an external cost to the society represented by the area SAQ. A social optimal production level at the price=p is represented by the point T, where social marginal costs are equal to price and not by A, where private marginal costs equal price.

Thus, the optimal price of domestic oil for the society should be lower than p when environmental concerns are taken into consideration. This is in contrast with the fact that the society may wish a higher price of oil when considering security of supply aspects. A price increase for domestic producers to p*, as in the previous graph, should therefore be weighed against the environmental concerns one might have.

2.3 Combining Security and Environmental Aspects

In the graph 2.3.1 the social marginal cost of the environment damage of domestic oil production is drawn as in the previous graph with MC(social)=price in R. The marginal social cost of import dependency is drawn as in the security graph, but now it starts in R rather than in A. This is because we take into consideration that domestic production should in fact have been lower than in A as it imposes an environmental problem on society. Thus, the marginal social cost curve representing the import dependency intersects the marginal (social) benefit curve for the society (demand curve) at U. This is higher up than point F in graph 2.1.1. Total social marginal cost curve will follow the curve C-S-R-W-U.

When we consider import dependency together with the environmental problems, consumption of oil should be lower (and the price higher, p' > p*) than with no environmental considerations. If the price equals p', the environmental costs to the society will be represented by the triangle SWV. Domestic output should be lower (represented by the point W), and not by Y as p' would yield in a free market where marginal social costs exceed marginal private costs by the distance YZ.

Thus, when both security and environmental aspects are considered, and with the world oil price at p, consumer prices should be raised to p'= p + t1 (t1 equals the distance UX). But producers' prices should equal p' - t2 (t2 equals the distance UW). The point W has to be on domestic producers' long-run supply curve, but can be both to the right (as in the graph) or to the left of point A, or in A itself as a special case. The position of W depends on the slopes of the two marginal social costs curves and the supply curve.

In the next Chapter we shall discuss some of the options at hand to achieve these socially desirable goals.

3 POLICY OPTIONS

Chapter two outlined that an optimal price of oil from a security of supply perspective is in conflict with environmental concerns and vice versa. The security problem can be considered along two dimensions. First to reduce the general level of dependency on foreign oil. Second, at any given level of imports, to reduce the damage by a possible disruption in supply, normally expressed by sharp increases in prices. In this Chapter we shall mainly discuss the role and use of an import fee, a gasoline tax and stock building as means to reduce the security problem connected with imports of crude oil in the United States.

3.1 Oil Import Fee

An import fee would raise the prices paid for all oil in the U.S.. This would lower demand and increase domestic production of oil. The costs to the economy of such an (in economic sense) overall inefficient way of producing would be large. On the other hand, because the U.S. is a very large purchaser, the fee would lower U.S. demand for oil and, thus, partially also lower the world price of oil. That would benefit oil consuming and be negative for oil producing allies. And, as we have mentioned in Chapter 2, increased domestic production may cause unacceptable environmental damages, that is if it is possible to increase production to any significant extent. If domestic production cannot be increased, the fee will distribute incomes from consumers to producers without getting much more domestic oil. In that case, the tariff should be justified by other reasons than security of supply. In a cost-benefit scheme the results of an import fee can in short be summarized as:

Benefits:

- Increased domestic oil production, exploration, reserve addition, and employment in the petroleum sector.

- Reduced U.S. oil imports, reduced import bill, reduced loss in case of a disruption.

- Reduced world oil prices, good for oil-importing allies like Japan and most European countries and most LDCs.

- Increased investment in capital equipment that has flexibility in fuel usage.

- Import fee receipts, reduced federal deficit.

- Increased flexibility in foreign policy towards the Persian Gulf area.

A tax on domestic production should also be considered more carefully than our simple scheme in Chapter 2. The U.S. has shown to be the no. one world high cost producer. The industry itself would probably rather argue that a subsidy is a more proper measure than a tax. Thus, politically it will be important which of the interests, security, the environment or something else, will be given the largest weight.

3.2 Gasoline Tax

An excise tax, e.g. at the size of t1, figure 2.3.1, could in a specific situation also realize an optimal result, when we consider only the security and environmental aspects. That is, if UX=VW, i.e. that point W exactly hits point A. If W is not in A, a gasoline tax will be sub-optimal, yielding too much or too little domestic production. Depending on the distance VW the excise tax will yield a larger, equal or smaller revenue for the government than the combination of a tariff and a tax on domestic production.

With the difficulties in determining the real external costs of domestic production and security concerns a tax may be not too far from t2. At least it lowers the environmental damage compared to if only a tariff were imposed. But normally it would not be optimal for both environment and security concerns. The costs and benefits can in short be summarized as:

Benefits:

As we see, many of the same goals are achieved with a tax as with

the tariff. The main difference is the effect on the domestic production/environment.

The effect for the treasury will depend on the magnitude of the tariff/taxes

and the elasticities of demand and supply. Any sharp conclusion cannot

be made as long as we do not make any attempt to quantify the costs and

benefits.

3.3 Conservation and Switching Policies

The demand elasticity for oil depends both on the development of the relative prices on other energies and the technologies that are used. By building more energy efficient cars, isolating houses and bringing on the market other cheap energies a high consumption of oil would be less of a problem. Thus, by making demand for oil more elastic, the structural dependency for oil will be reduced either in the short or long run or both.

Also increased energy prices would encourage consumers to use less energy and be more efficient in its use. This will happen both with a tariff and a gasoline tax. Which of them is the most appropriate one, if any, depends on the elasticities of supply and demand, and other goals mentioned.

3.4 Stockpiling

Rather than relying on fiscal policies to reduce dependency on foreign oil, as e.g. most European OECD countries do, the U.S. has let market forces work on their own to a much larger extent. On the other hand, in the U.S. stock policies seem more important than in Europe. The next table shows that while total OECD stocks have increased some 844 million barrels since 1973, the U.S. share of the increase was ca. 586 mbd. This is an increase of 50 per cent compared to the U.S. stock level in 1973, a much larger increase than in Europe. Japan, however, has also increased its stock with some 50 per cent in the period. In relation to the share of total OECD oil imports, these two countries have a relatively much higher inventory of oil than do Western European economies.

3.4.1 Private Stocks and the Strategic Petroleum Reserves (SPR).

Most businesses trading and/or refining commodities need inventories to meet temporary fluctuations in production and sales. The size of the inventory depends on ordered quantity and variations in supplies and demand. In low-demand periods inventory is build up, and drawn down when demand is high. Increased variations in demand and/or supply as well as increased uncertainty increase the need for stocks.

In addition to 'normal stocks', mentioned above, a firm can also build inventory for speculative purposes. This is not done out of a need to fulfill delivery obligations, but to make profit on speculating on changes in the price. Speculative inventory behavior implies that firms should build stocks when prices are rising, and sell when they are beginning to fall, corrected for the administrative and capital costs of keeping the stock. A speculative stock-holder should build inventory when the difference between expected future prices and current prices exceeds the costs of storage.

The third types of stocks are the Strategic Petroleum Reserves (SPRs) owned by the government. U.S. official policy, as set out by the U.S. Department of Energy, is to confine government intervention in a disruption to using the SPR. The SPRs would be an additional source of supply, which also would dampen the rise in prices in the case of a disruption. Thus, total stocks (S) in the U.S. can be expressed as the sum of 'normal' private stocks (Sn), speculative private stocks (Ss) and the governmental owned SPRs (Sg).

3.4.1.1 S = Sn + Ss + Sg

How big a share of total stocks does each of these three components

constitute? The SPRs are easily observable as separate figures shown in

the next table. The SPRs building started in 1977, and has been increased

considerably since OPEC II. It reached the level of 551 million barrels

on the average in 1988, and will probably be in the range of 560-575 million

barrels in 1989. In 1988 the SPRs represented about 1/3 of total U.S. stocks.

With increased volatility in the oil market in the period 1973-82, the 'normal' private inventory should, according to our discussion, be somewhat higher than in the pre-1973 period. As we see from the figures in the previous table, private stocks were especially high in the late seventies, and then back to the 1973 level from 1983 up till today. The last 5 year consumption has been at the level of the pre-1973 years. Prices have been falling as well, indicating low speculative stocks.

This is of course a rather simplistic way to determine the size of 'normal' stocks. Nevertheless, it gives some indication that it is first of all in volatile price situations that speculative stocks are built. Even then it is difficult to determine whether increased stocks are due to the 'normal' need to balance increased variations in supply or to speculations in order to gain profit from a sale at a later point in time. The arguments mentioned above and the figures in the previous table indicate that the overwhelming part of private U.S. oil inventory is due to the need for fulfilling obligations to customers and rather less dependent on the expected price development.

3.4.2 The Effects of a Release of the Strategic Petroleum Reserves

Oil prices can increase for two reasons. Demand increases because of higher consumption of inventory build-up. Or supply can be reduced due to production cuts (i.e. by OPEC countries) or some other sort of disruption. A disruption worsens when production is close to capacity, as the elasticity of supply normally is expected to be more inelastic at production figures close to capacity.

Before 1985 there were two prices of oil. The contract price was the one that most oil was sold for. However, this price was too "rough" to equate the market to the full extent. Instability and the difficulties in estimating the market exactly, justified the spot market. The spot market acts as a barometer of disequilibrium to the contract price and it will also express expectations of the future market development. After 1985 oil is not sold according to fixed contract prices, but the future market has, to some extent, replaced their function. Still there is a spot price for day-to-day trade. But the future prices more rapidly adjust to supply and demand conditions in the market and expectations about the future development than did contract prices. The difference between spot and future prices today, thus, will be less than the difference between spot and contract prices before in periods with volatile prices.

The effect of stocks on prices is first of all to dampen the immediate shock. It is hard to see that the magnitude of the stocks can large enough to affect dependency structure for oil. Hubbard & Weiner (1982) divide the effect of a stock (SPR) release in three: a) The direct effect reduces demand for OPEC output, and thus the magnitude of the spot price changes. The mitigation of the spot price change also reflects some mitigation of the future prices. b) The feedback effect represents the reduced cutback in consumption caused by a lower price than the market would have yielded without a stock release. Obviously, the feedback effect works against the direct effect. c) The international interaction effect depends on how foreign stocks react to SPRs releases. If other countries cooperate, the SPRs and other countries' stockpiles are released simultaneously. This serves to magnify the effect. Competition implies that as the U.S. draw stocks are built up, foreign stocks may be built down. This serves to mitigate the effect. But in addition to these effects, a fourth effect may be added; d) the domestic production effect. Keeping down the prices implies reduced increase in domestic oil production compared to no intervention. The sum of these four effects gives the net result of a SPRs release.

Is there any relationship between the SPRs and the private stocks? Consider a situation where prices rise rapidly and the government starts to draw on the reserves. The draw-down increases supply in the market and tend to dampen spot prices as well as the volatility in them. Less price increase and volatility serves to lower both normal and private stocks. Thus, Sn and Ss will both increase less than with no SPRs release. The SPRs releases serve to reduce private inventory accumulation. Similarly, when SPRs are built the partial effect on both private normal and speculative stocks are that they will be increased as well, because SPRs build-up increases demand and thus prices. Therefore, SPRs build up tends to increase total stocks more than just the build-up itself.

Similarly, a SPRs draw tends to lower total stocks more than just the reduction in the SPRs. However, the reduced volatility in prices does not mean that SPRs necessarily manages to stabilize them totally. Therefore, when prices are increasing, speculative stocks may be built at the same time as SPRs are released. It may thus look like they absorb SPR-stocks because the net effect on the prices are that they still are increasing. Furthermore, Sn will also increase at the same time as SPRs are released in such a situation, but less than with no intervention. From table 3.4.1.2 we see that when SPRs were built up in the eighties, private stocks were built down. The SPRs building is a result of a policy to increase the ability to respond to spot price changes. The reduction in private inventories can be explained as a result of falling real prices of oil in the period and a greater stability in the market, rather than as a result of SPRs increases.

Because private stocks are built during a price shock, demand is further increased and they may therefore tend to worsen the crises. This happened in 1979-81, when the cut-backs in Irani and Iraqi production were met with increased private stock-building. If the initial price increase from the shock is p., the mitigation effect on the price increases as a result of SPRs release ?dp./dSg?, the price increase after the release of the SPR, p.(new), can be expressed as:

In the crises needed for SPRs to be drawn down, i.e. a declaration of emergency by the US President, it seem difficult to expect that SPRs releases can change the direction of the price development, i.e. that ?dp./dSg? > p.. To manage this, stocks would have to be very large. However, as SPRs releases mitigate the price increase they also changes the magnitude of the private speculative stock-building.

As speculative stocks are built on the expectation of the price development, SPRs releases may, however, affect these expectations to such an extent that speculative stocks are sold when SPRs are released which would magnify the effect. If SPRs should be drawn at minor shocks, ?dp./dSg? may become sufficiently close to p. that it will be profitable to release the speculative stocks (if the costs of holding the stocks exceed the difference between p. and ?dp./dSg?. Therefore, the effect of use of SPRs in a "sub-trigger" system seems more unclear than in a "trigger" system, i.e. a major price shock (see Chapter 3.4.3).

In a major price shock, speculation is important to investigate in order to understand the price dynamics of the oil market during a disruption and to determine at which level the SPRs should be drawn. It is also important to be aware of the increase of "normal" stocks in a disruption situation. However, if we assume the shock is big enough so both normal and speculative stocks are built in a crisis even if SPRs are released (p.(new) > cost of holding stocks) and that they thus worsen the crisis, a tempting question can be raised: Can the government refrain companies from making spot-market purchases in such a situation? Obviously, governmental interest in overall stability may in such a situation conflict with the companies' need for increased inventory to fulfill obligations as well as their speculative interests.

3.4.3 Stocks, Energy Security and International Cooperation

An inventory of oil can serve as an alternative source of supply, which rapidly could be put on the market (unlike increased domestic production). Except for the speculative stocks, they are some sort of a insurance protection against disruption. The optimal size of the stockpile should minimize the sum of expected damages plus the cost of stock-piling. In marginal terms, the costs of the last barrel stored (capital and administering costs) should equal the costs of the expected damage from not storing it.

Both the level of the stock and the draw-down (or build-up) pattern in times of crises, will affect the final outcome of a price shock. The IEA provisions from 1974 implied that if more than 7 % of consumption were disrupted, the stocks should start to be withdrawn ("triggered"). This may be thought of as what we have called a "major" shock. If all IEA countries coordinate their use of stocks, the total effect on the market may be significant but the costs for each country less. The international interaction effect is magnified. By such a coordinated policy each country will be better off than if they should act alone. The magnitude of the benefit is debatable, but the surveys done on the subject represent a consensus that the effect is substantial.

The main features of the IEA cooperation in order to lower short run

demand include:

b) The sharing mechanism in case of a crisis is essentially dormant until it is determined that a severe disruption really has occurred. As mentioned, at least 7 % of total consumption compared to the last year's use, has to be disrupted.

c) If a crisis occurs, member countries have to reduce consumption by

7 %, thus imports by more than 7 % and the rest shall be made up by drawing

down reserves. Thus, this is a combination of stock policy and some other

means to reduce demand (for example rationing).

4 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

If a country becomes sensitive or vulnerable in it's imports of crude oil, the imports (and consumption) have an added cost which is not reflected in the market place. As was shown in 2.1, a 'free' market generally results in too much dependence on imports. Self-sufficiency is, however, inefficient and the private costs of increasing domestic production so this could happen exceed the social benefits. An embargo is not a certain event, it may not even occur. Thus, some imports are desirable. The optimal amount of imports will depend on the likelihood that an embargo should occur, as well as the intensity and duration of it. This is reflected by the slope and shape of the marginal social cost curve for import dependency.

We have touched upon some policies to deal with this problem in Chapter 3. It is in the context of our discussion important to be aware of the fact that few countries view the physical dependency on oil as a severe problem. In the oil crises we have had, oil has been available, but at a much higher price than was acceptable without bringing on serious damage to the economy. Even without any physical import from insecure sources, a country may still face a security of supply problem from the (volatile) price prevailing in the world oil market, partly determined by variations in or decisions made by "insecure" suppliers.

The way to deal with the problem depend to some extent on the nature of the crisis. There are smaller and larger price fluctuations and they can last for a very short time or for longer periods. We have discussed the problem along two lines; the short term actions to cope with disruptions when they occur (as stock policies can be a part of) and longer term measures to reduce the overall dependency (as tariffs, taxes and conservation measures are). Thus the measures are in many respects not alternatives, but rather complementary to each other.

Among the policies we have discussed, immediate shocks can best be dealt with use of inventory. Coordination of a collective action in drawing stocks through the IEA is especially important in order to magnify the effect of the stock draw. We have argued that the SPRs and private speculative stocks are not related directly to each other. In a major price shock, a draw on the SPRs serves to mitigate private stockbuilding through the dampening of the price increases. But as speculative stocks are built when prices increase, which is the time when profits can be made, private stocks will still be built when SPRs are drawn and vice versa. Statistically one may therefore find some correlation between SPRs draw and speculative private stockpiling, because of their inverted reactions to rapid changes in prices. At smaller shocks, however, the possibility that speculative stocks should be sold when SPRs are released are larger. That would reinforce the effects of the SPRs draw. When prices are expected to stop rising or even decline (the rise in prices is smaller than the costs of holding the inventory), speculative stocks will be built down.

The longer term responses are aimed at reducing dependency by restraining demand growth and possibly encouraging domestic oil production. Increased domestic production may, however, meet objections from environmentalists. Furthermore, statistics on U.S. production (and reserves) may indicate that supply is rather inelastic to changes in pr>

Obviously there are good reasons to encourage conservation and investment in capital equipment with flexibility in fuel usage. The controversy remains whether one should use a tariff or a gasoline tax, some combination of both or none of them, in order to restrain demand.

The model in Chapter 2 argues that a combination of a tariff and a tax on domestic production to reduce environmental damage is optimal. A gasoline tax would, in the model, only be optimal in the special situation when marginal social costs to the environment of increased domestic production equal marginal social costs of import dependency. However, either values are possible to measure statistically.

In the choice of policy, factors outside the model have to be drawn into consideration as well. We have mentioned some of the most important ones in Chapter 3. These factors are both of micro- and macroeconomic and national and international political kind. It is outside the scope and length of this paper to calculate the costs and benefits of the pros and cons of the strategies listed in Chapter 3. However, we shall make an attempt to summarize the effects of the three options we are discussing.

In table 4.1, the effects of the alternative policies on important variables

are given pluses (+) and minuses (-). A gasoline tax is thought to exactly

offset the tariff's effect on price of oil in the domestic market. Thus,

a tariff rising domestic prices 5 $/bbl is the alternative to a gasoline

tax also rising domestic prices 5 $/bbl.

An import fee raises domestic oil price both to consumers and producers. A gasoline tax, on the other hand, raises the price to consumers but leaves the price to producers at approximately the same level. Thus a major difference between the two is their effect on the producers. An import fee will raise domestic production (at least marginally), a gasoline tax probably decrease it marginally (because of the lowering of world oil prices).

a) Long- and short-term security of supply. Dependency on foreign oil will be reduced more with an import fee than with a gasoline tax. The magnitude of the dependency will in its turn have an effect on the security of supply in a given situation (which is defined in Chapter One as a question of changes in crude oil prices). However, the fiscal policies are long term goals. Neither a tariff nor a gasoline tax helps much for the immediate shocks. In a specific emergency situation stock policies are better because of the immediate provision of new supplies.

b) The budget. A gasoline tax will yield higher revenues to the government than an equally sized tariff, as the tax also gives incomes from domestically produced oil. The costs of keeping the SPRs give them a minus in the budget.

c) Environment. For the environment a gasoline tax is better than an import fee as the latter increases prices to domestic producers. Increased production as a result of a tariff may impose more environmental damage. However, the effect of reduced demand as the result of the import fee may offset its effect on increased domestic production because of the inelasticity of supply. In that case the effect of an import fee will be positive for the environment.

d) Administrative and political feasibility. It is difficult to see any clear difference in the costs and difficulty in administering the alternative policies. However, as SPRs obviously have a political support in the U.S., it is more doubtful whether such support exists for the fiscal alternatives. With president Bush's promise of "no new taxes" both the gasoline tax and the import fee are given a minus.

e) Foreign oil exporters and importers. As the import fee increases U.S. domestic production (at least marginally) foreign oil exporters will like the tariff less than a gasoline tax. Foreign oil importers, however, will appreciate increased U.S. domestic production as lower U.S. imports keep world prices down, and thus prefer the import fee to the gasoline tax. The SPRs stabilizing effects may be perceived to be positive among oil exporters as they also benefit from stability. However, SPRs will normally be used to reduce prices (in the short term) and it is more likely that oil exporters may (at least partially) be better off without SPRs. Oil importers would benefit from the SPRs, as the U.S. itself.

If we stick to the argument that domestic productions should not (for environmental reasons) or could not (because of inelasticity in supply and reserve situation) be increased, there may be reasons to exclude the tariff alone as the policy device. A tariff combined with a tax on domestic producers may seem politically too complicated in spite of its superiority in the sense of economic efficiency.

A gasoline tax seems to be of less controversy in foreign policy terms. It may be perceived more as an internal political device than being directed against oil-exporting nations. In Western Europe the gasoline taxes are much higher than in the U.S. which also make this option easier politically.

Whether the political arena may accept a new tax or a tariff is an open question. As long as a gasoline tax would lower world oil price (to some extent) and thus hit domestic as well as foreign producers, it should, however, be possible to give the domestic oil industry some economic advantages as compensation for their losses. That may ease the industry's political pressure against such a tax. Still, the Bush Administration, as did Ronald Reagan, will probably avoid both a tax and a tariff as long as possible.

What about doing nothing? Consumption will probably continue to grow, conservation will not be encouraged and the U.S. may face very high import bills if and when the next price shock comes. But part of the solution on the security problem may come from the market itself if the prices in the world market continue their gradual increase and thereby dampening off consumption.

Reduced sensitivity and vulnerability, even reduced dependency, may

in and by itself deter OPEC countries from causing a disruption

situation. With sufficiently low security risk for the consuming countries,

prices may not increase enough to compensate for the lower volumes over

the relevant time horizon for the Organization of Oil Producing Countries.

The value of the deterrence effect should be taken into consideration (the

premium paid for the shock never to happen) when calculating the optimal

size of the tax and the stocks. The sum of Western European fiscal and

U.S. and Japanese stock policy today represents in fact a combination of

the use of SPRs with high gasoline taxes. However, the size of the optimal

tax depends on the size and draw-down pattern of the SPRs and vice versa.

If today's situation is optimal, for the OECD as a whole or for the U.S.

in particular, this seems more accidental than deliberate.

REFERENCES

Austvik, O.G., 1986: Søkelys på mekanismene i oljemarkedet NUPI report no.110. ISSN 0800-0018.

British Petroleum, 1988: BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

Broadman, H.G. & Hogan W.W., 1988: "The Numbers Say Yes", The Energy Journal no.3.

Dasgupta, P.S. & Heal G.M., 1979: Economic Theory and Exhaustible Resources, Cambridge University Press.

Goulder, L.H., 1989: "Environmental and Natural Resource Economics", Course at Department of Economics, Harvard University.

Hogan W.W. & Mossavar-Rahmani B, 1987: Energy Security Revisited. Harvard International Energy Studies no.2. Energy and Environmental Policy Center, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Hubbard, R.G & Weiner, R, 1982; The 'Sub-Trigger' Crisis: An Economic Analysis of Flexible Stock Policies, Discussion Paper H82-07. Energy and Environmental Policy Center, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

---, 1983; Oil Inventory Behavior: An Empirical Analysis of Public-Private Interaction", Discussion Paper H83-02. Energy and Environmental Policy Center, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Gonzalez, R.J,, Smilor, R.W. & Darmstadter J, 1985: Improving U.S. Energy Security. Ballinger Publishing Company.

Keohane, R.O. & Nye J.S., 1977: Power and Interdependence; World Politics in Transition. Little & Brown.

Lumsden, G. Q., 1989: "The International Energy Agency - Looking Into the Future. Is the IEA Serving its Purpose as an Instrument for Western Oil Cooperation?" in Austvik (ed.) Norwegian Oil and Foreign Policy, Vett & Viten.

Manne, A.S. and Schrattenholzer, L, 1987: International Energy Workshop. Overview of poll responses. Energy Modelling Forum, Stanford University July.

Nesbitt D.M. & T.Y. Choi, 1988: "The Numbers Say No", The Energy Journal no.3.

Roland, K., 1989: "The Driving Forces in the Oil Market in a Short- and Long-Term Perspective" in Austvik (ed.) Black Gold: Norwegian Oil and Foreign Policy, Vett & Viten.

Schelling, T., 1978: Micromotives and Macrobehavior. W.W. Norton.

Schmitz, A., 1984: Commodity Price Stabilization: The Theory and It's Application. World Bank Staff Working Papers no. 668.

Tietenberg, T., 1988: Environmental and Natural Resource Economics. Scott, Foresman and Company.

Tussing A.R & Van Victor, S.A., 1988: "Reality Says No". The Energy Journal no.3.

U.S. Department of Energy, 1984: Sale of Strategic Petroleum Reserve; Standard Sale Provisions. Federal Register, 10CFR Part 625.

---, 1987: Energy Security; A Report to the President of the United States.

---, 1988: Monthly Energy Review, October.